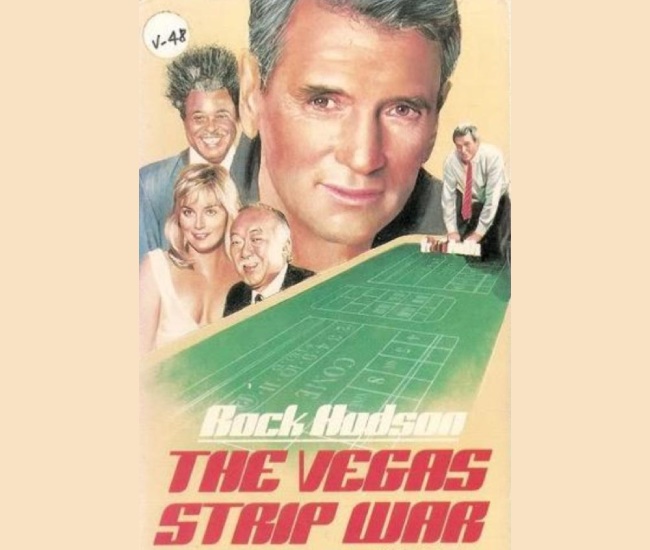

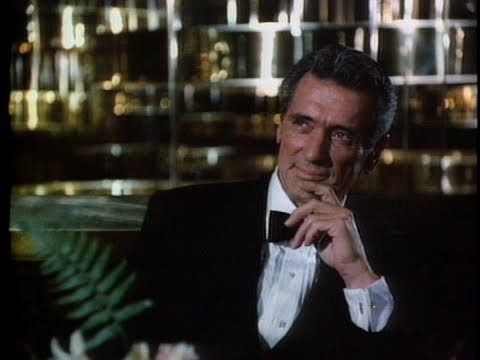

Despite the fact that Rock Hudson is one of my all-time favorite actors, I had been on the fence about whether to watch what was supposedly his last feature film, a largely forgotten made for TV movie called The Vegas Strip War. It was filmed in 1984, only a year before the Hollywood legend’s death from AIDS would send shockwaves throughout the world. It’s visibly apparent by Hudson’s gaunt appearance and pained demeanor in this film that his illness was taking a toll on him. Part of me didn’t want to watch this movie because I wanted to remember him the way he was through most of his career, confident and jovial as he traded humorous and playfully romantic banter with actresses like Paula Prentiss and Doris Day… or even the charismatic and distinguished statesmen-like roles he took on in his later career in memorable TV miniseries’ like The Martian Chronicles and World War III,(both of which I own on DVD).

Another part of me didn’t want to watch The Vegas Strip War out of fear that seeing Hudson in his state of declining health would exacerbate my own longstanding losing battle with hypochondria and contribute to my anxiety over the ominous plethora of all-too-real undiagnosed health conditions, which are inevitably looming just beneath the surface even as I’m typing this. (Indeed, Hudson’s “physique” in the film often bears an uncomfortable resemblance to my own.) Nevertheless—neuroses be damned!—I forced myself to watch the movie anyway, and it was definitely worth it.

In The Vegas Strip War, Hudson plays a well-liked casino mogul named Neil Chaine who gets double crossed and forced out of his role at The Desert Inn by his ruthless business partners. The reason given is that the casino has been denied a gaming license in Atlantic City, NJ because of Chaine’s association with Jimmy Weldstrom, a man who supposedly has ties to the mob. However, this is more like a opportunistic pretext, as his business partners appear to be primarily motivated by greed and spite. The more sinister and cold-hearted of these partners (Gray Ryan, played by Madison Mason) seems to have been suspiciously (and probably intentionally) made to look like a caricature of 1980’s Trump, right down to the hairdo.

Down and out, looking for redemption (and perhaps revenge), Chaine purchases the struggling Tropicana hotel/casino in the hopes of revitalizing it and settling the score with his former associates, attempt to sabotage his new venture every step of the way. Pat Morita (of The Karate Kid fame) has a small supporting role as Yip Tak, a friend of Chaine who is hired to bring in the kind of wealthy Asian gamblers who can potentially increase the casino’s revenue. I already mentioned that the film’s main antagonist is modeled after Donald Trump, but he’s not the only iconic Vegas figure lampooned here. James Earl Jones plays an unscrupulous boxing promoter named Jack Madrid who is clearly supposed to be parody of Don King. This character provides much of the film’s comic relief, with his bombastic statements and shameless dishonest negotiating tactics. He also frequently levels unfounded accusations of racism, which the other characters simply roll their eyes at and laugh off. It’s retroactively refreshing to see such frivolous accusations in 1984 brushed off as the preposterous shakedowns they are. In today’s world they would be taken deadly seriously, and there would be heavy consequences for even questioning them, let alone mocking them. I don’t want to disgust my readers, but there is a particularly amusing scene where Jack Madrid accuses Sarah Shipman (a casino “hostess” played by a youthful Sharon Stone) of disliking him because he’s black, only to look out the window as she steps off the airplane and locks into a sensual embrace with an African American gentleman whom she had previously described in conversation as “a new doctor, [a] star in pediatric research [at] Stanford Hospital.”

These days, it’s hard to imagine celebrities like Sharon Stone as anything but shrill political activists and mouthpieces for the neoliberal establishment, who spend much of their time on social media bashing anyone perceived as being remotely to the right of them. It’s difficult to even view or appreciate these celebs as actors anymore. Though her character in The Vegas Strip War is essentially the same confident, driven, witty and no-nonsense “bitch” type she plays in almost every movie, it’s impossible here not to acknowledge what a gifted actress and undeniably beautiful woman Sharon Stone is. She looks absolutely gorgeous in this movie. It’s easy to see that she was destined for mega-stardom (and why the normally stoic Thomas Magnum was so devastatingly heartbroken after tragically losing her in the classic two-part Magnum P.I. episode, Echoes of the Mind). In The Vegas Strip War Stone plays Rock Hudson’s romantic interest, in what could be described as a precursor to the role she would later play in Martin Scorsese’s 1995 hit, Casino.

This is undoubtedly a minority opinion, but I think The Vegas Strip War is better than Casino, at least in few key aspects. Unlike in Casino, where everyone is constantly trying to showoff how badass, stereotypically Italian and macho they are, The Vegas Strip War takes a cynical and often satirical view of corporate casino culture, exploring the tedious world of board room politics, manipulative power plays and licensing bureaucracy. On a deeper level it deals with how the integrity of human relationships is pressure-tested by the cold, cruel and utterly mundane realities of business.

Aesthetically, the setting has a rather bleak look to it. The lighting is often dim, providing an appropriately depressing backdrop for the characters’ seedy activities and unfortunate situations. This is not one of those fun or glamorous depictions of Las Vegas like we see in films like Austin Powers, Ocean’s Eleven or Diamonds Are Forever. Having said that, it does capture a wonderful era of Vegas that has always appealed to me and which many people are nostalgic for. Knowing what a ghetto shithole Las Vegas has become in the last decade makes it almost painful to watch this and constantly be reminded of “what they took from us.”

There are a couple of profound scenes in The Vegas Strip War. One of them takes place at a contentious hearing with the gaming commission, where Hudson gives an impassioned defense of due process and rails against the practice of “guilt by association.” Contemporary political dissidents and those who have experienced “cancellation” will undoubtedly find the exchange relatable. In another scene, Hudson and Stone’s characters are visiting (as vacationing tourists) Alcatraz in San Francisco. While in a prison cell with her, he peers out a small window and paraphrases a line from Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol:

“That little tent of blue which free men called the sky.”

(However, the actual line from Wilde is supposedly Upon that little tent of blue which prisoners call the sky)

Hudson then remarks that Oscar Wilde “was locked away because he was homosexual.” Is this bit of dialog Hudson’s subtle way of publicly coming to terms with his own sexual orientation? Is the substitution of the phrase “free men” a simple error, or an intentional comedic quip referencing the fact that though Hudson has never been technically imprisoned for his sexuality, he identifies with Wilde’s experience? Perhaps it’s a commentary on how the terms “free man” and “prisoner” can be interchangeable depending on the circumstances. A person may be legally free but still feel like a prisoner, unable to live openly as their true self.

The third important scene occurs toward the end of the movie (spoiler!) after a group of wealthy Chinese gamblers have won several million dollars and essentially bankrupted the Tropicana. Neil Chaine is directed out to the pool where his old friend Jimmy Weldstrom is there waiting, tempting Chaine with a financial offer to save his business if Chaine will agree to do business with the mob. In rejecting the offer, Hudson gives a powerful monologue. Though he had always denied (including in the hearing with the gaming commission) any knowledge of Jimmy having ties to the mob, he admits he had been lying to himself and that deep down he always knew:

“It’s not your fault. You never really masked who you are. It makes me realize…how far I am from heaven.”

Unexpectedly, Rock Hudson gives one of the best performances of his career in The Vegas Strip War. He brings depth, sensitivity, humility and vulnerability to the character of Neil Chaine, elevating this seemingly throwaway movie of the week into something hauntingly inspiring. Hudson’s weakened physical appearance adds a layer of realism to his performance. When Neil Chaine is at various low points, struggling to persevere after being dealt a successive series of backstabs and unlucky blows, he finds the will to push forward, and he does so genuinely looking as if his life depends on it. The tenacity Rock Hudson displays in this movie speaks well of him, not just as an actor or as a professional but as a person. A legend from Hollywood’s golden age who was approaching an almost certain death, he had little to gain from doing this movie at all. Yet, rather than merely go through the motions, he resiliently put everything he had into it and went out a winner.